The Art of Hypervisibility

While we tend to equate the visibility the online world offers to young people with increased exposure to cyberbullying, harassment and violence, adolescent Black girls are turning that assumption on its head by exploring creative new approaches to digital self-expression.

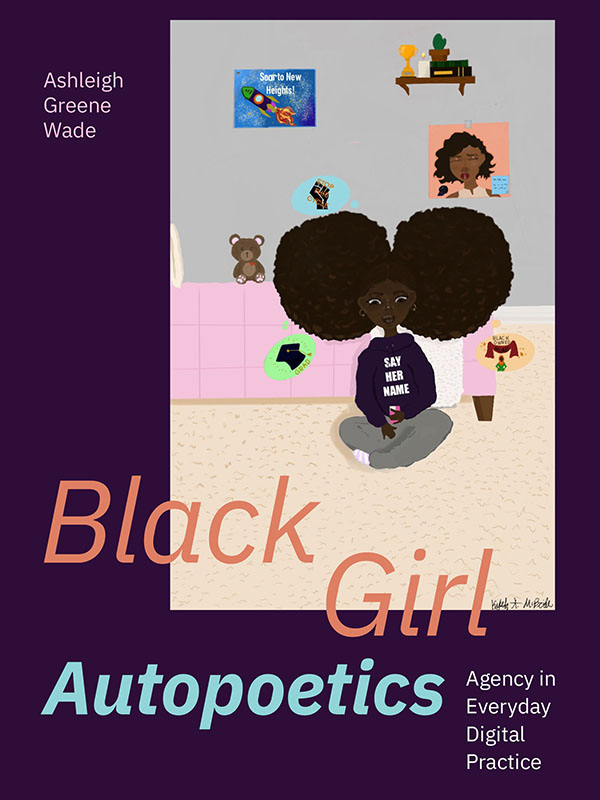

In her forthcoming book, Black Girl Autopoetics: Agency in Everyday Digital Practice, Ashleigh Greene Wade, cultural ethnographer and assistant professor of media studies and African American studies with the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, examines the innovative ways Black girls are using digital spaces like social media for self-expression and cultural activism to create a more life-affirming and empowered tomorrow for themselves.

Read an excerpt from this important new work that reviewers are hailing as a must-read book for those interested in understanding our digital future.

From Black Girl Autopoetics: Agency in Everyday Digital Practice

“I love posting pictures of myself! I was never confident growing up and now that I genuinely love the way I look, I always want to show the world. I feel as though my beauty makes people uncomfortable, so I always post myself to make others who don’t feel the mold of beauty feel more confident.” – Bella, 16

When I first decided to do ethnographic work to complement my readings and interpretations of Black girls’ digital content, I spent quite a bit of time talking to school administrators and youth group leaders as part of the process to recruit Black girls to observe and interview. I wanted to have an opportunity to at least talk with Black girls about my work, and since educational spaces play such a central role in their lives, I knew I would need to go to these spaces to find Black girls. As a former secondary school teacher, I also knew that I would need to explain my research and recruitment process to educational administrators. In my conversations with school personnel, almost all of them had in common a deep misunderstanding of the work I sought to do. Upon explaining to school administrators and other educational practitioners that I wanted to talk to Black girls about their social media engagement, most of them interpreted my role as one of policing: these educators thought I would be telling Black girls what they should and should not post on social media. The initial enthusiasm for having me visit classrooms and summer programs quickly faded once faculty and administrators realized I was there to learn from Black girls, not to impose discipline.

One conversation stands out in my mind as both characteristic of how educational practitioners tended to view my research objectives and representative of attitudes about Black girls’ digital media use more broadly. In an effort to set up a discussion group, I met with an educator, who I will call Kyle. Kyle, a white man, had extensive educational administration experience and seemed to have a good rapport with the students at the predominantly Black school he led. I met with Kyle to discuss the possibility of using the school he supervised as a site for discussion groups with girls. After I explained to him that I wanted to understand more about Black girls’ online content, he said, “They’re probably just posting selfies and sexting.” My facial expressions tend to betray my attempts to keep my thoughts to myself, so I had to put forth extra effort to - as we say in AAVE - fix my face. I must have failed because Kyle went on to clarify that he did not think that teenagers, especially ones in middle school or early high school, had the maturity to post anything deep. There are at least two problems with Kyle’s assumptions, both of which revolve around his positionality as a white man. First, it is racist to assume that Black teenagers have no depth. Second, it is misogynoiristic to characterize Black girls as hypersexual narcissists. Even if Black girls are “just posting selfies and sexting,” reducing these acts to a form of shallow self-absorption instead of trying to contextualize these alleged behaviors flattens Black girlhood into a one-dimensional existence.

At first glance, Bella’s comments that open this excerpt seem to confirm at least part of Kyle’s suspicions. However, Bella’s motivation for posting images of herself goes much deeper than the supposed vanity people like Kyle associate with selfies. I first encountered Bella’s Instagram account in 2016 as I perused the website of a non-profit organization devoted to the lives and well-being of Black girls. […] Bella had listed her publicly available Instagram account in her profile, so I began looking through her prolific curation of digital content, finding images ranging from selfies to excerpts of her theatrical performances to photos of activist organizing. Interested to learn more about the contexts and motivations behind Bella’s posts, I sent her a direct message (or DM) via Instagram. The exchange that ensued was both fascinating and enlightening.

Bella and I wrote back and forth to each other about uses of social media. She shared details about her school, friends, family, and values with me. By the age of sixteen, Bella had a grasp of Black feminist theories that I did not develop until graduate school. Many of her Instagram posts highlighted the importance of intersectional approaches to feminism, and she prided herself as someone who understands the inextricability of her Blackness, gender, and sexuality. Bella found queer community in her friends at school, which was essential to her personal development since she had not yet come out to her mother. […] Of all the things Bella and I discussed as having an impact on her social media content, body image played an especially salient role in her online presentation. Even though Bella admitted not being comfortable posting explicitly about fatphobia, her display of her own body (positivity) as a testament of self-love and confidence presented a challenge to the overall stigma placed on fat (Black girls’) bodies. Instead of trying to shrink herself, Bella used her Instagram page to post hundreds of images of herself, oftentimes dressed up, having fun, and accompanied by witty captions. Because Bella’s body size does not conform to hegemonic beauty standards, she makes herself hypervisible by posting hundreds of selfies online. In doing so, Bella flips the script about fat bodies - presenting them as lovable, desirable, and beautiful. As Bella indicated in the opening quotation, posting pictures of herself was part of a journey of self-acceptance despite the pervasiveness of externally imposed definitions about what it means to be a fat Black girl. Kyle’s characterization of Black girls posting selfies and sexting as narcissistic and superficial contrasts Bella’s motivations to post pictures of herself in order to declare value for fat Black girls. This discrepancy illustrates how the paradox of hyper(in)visibility manifests in everyday Black girlhood.

The paradox of hyper(in)visibility refers to the conditions that make Black girls simultaneously hypervisible and hyper-invisible. Misogynoir provides fertile ground for this oxymoronic reality through rendering Black girlhood both excessive and devoid of value. On the one hand, the circulation of Black girls’ images, whether by Black girls themselves or external actors, makes them hypervisible, especially within sociocultural contexts that require Black girls to draw as little attention to themselves as possible. On the other hand, while Black girls’ images circulate, their subjective intricacies get lost in the reductive generalizations people make about them as a result of not truly seeing, hearing, or knowing them beyond their images, hence the hyper-invisibility side of the paradox. Bella’s Instagram offers one example of how Black girls negotiate and/or play with the (hyper)visible aspect of the paradox of hyper(in)visibility. […]Black girls’ acts of becoming hypervisible not only operate as a refusal of modesty and docility but also as a refusal to accept the designation of Black girls as the problem within an anti-Black image regime that renders them hyper(in)visible. In these ways, Black girls’ use of hypervisibility becomes a tool of self-making or Black girl autopoetics.