‘Beacon of Hope, Blueprint for Activism’: Sample Julian Bond’s Speeches Online

Julian Bond, the late civil rights icon who taught at UVA for 20 years, left his papers to the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library in 2008, hoping the documents would be “a useful resource in helping shape future thinking about the civil rights era.”

Now, a selection of more than 100 of his speeches are accessible online through the Julian Bond Papers Project, an ongoing effort of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies and the Center for Digital Editing. The project received funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Bond taught at UVA from 1992 to 2012 after a semester as a visiting lecturer. Since 2018, the project team of director Deborah E. McDowell, managing editor Laura Baker and project manager James Perla have trained 12 student research assistants to digitize and provide quality assurance of documents. In addition, 400 community members, both during public events and online, have volunteered to transcribe Bond’s speeches. Altogether the project has transcribed more than 10,000 pages and digitized close to 13,000 images.

With such an abundance of material, the team decided to make documents available in stages, starting with his speeches.

“We noticed that the topics he engaged in the speeches – many of them written in the ’70s and ’80s – remain pressing to this very day,” said McDowell, a Woodson Institute professor and Alice Griffin Professor of English. Calling the topics “pillars of Bond’s work,” she cited speeches about educational equity, voting rights, student activism, health care, the fragility of democracy and environmental justice.

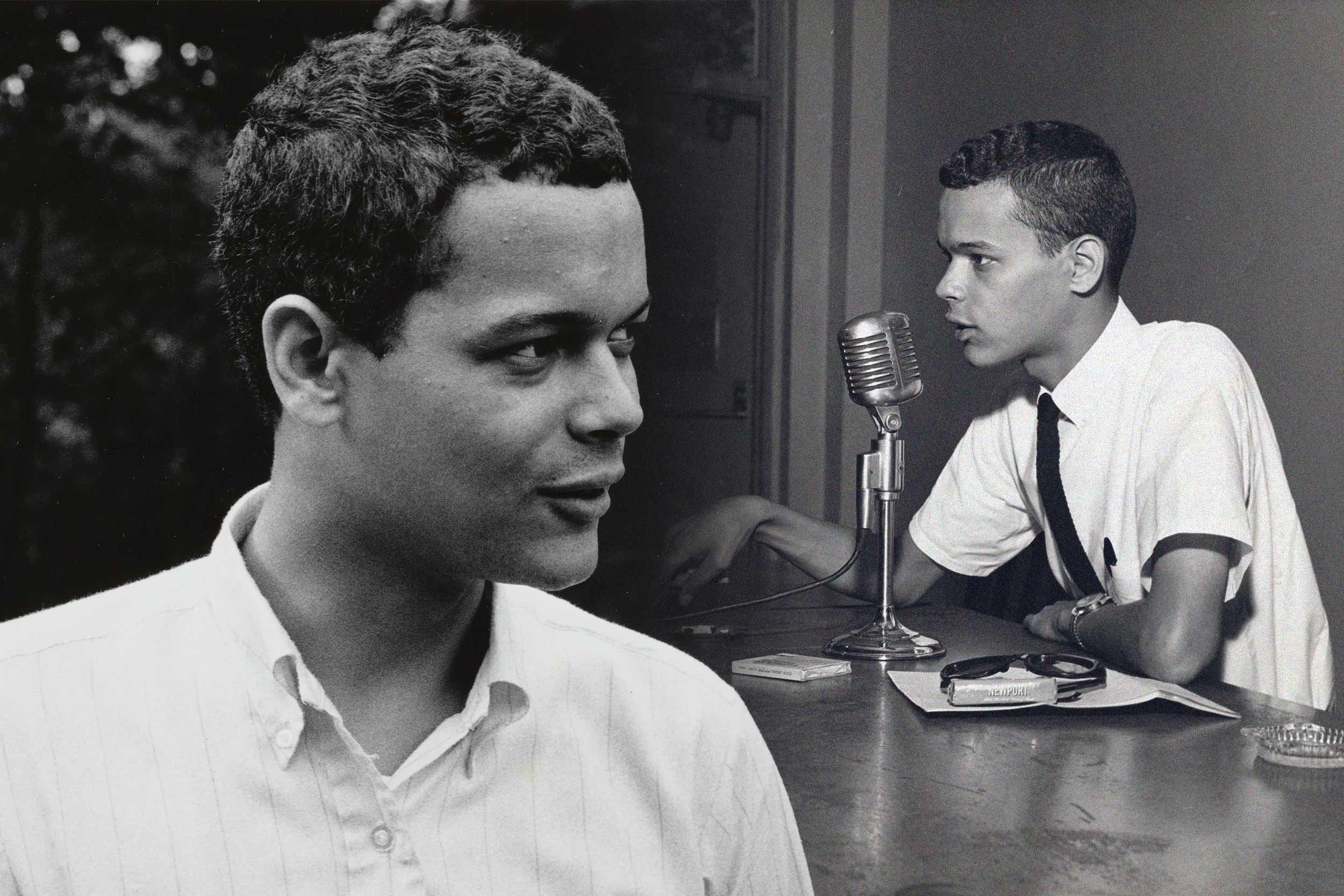

More than 100 of Bond’s speeches are accessible online through the Julian Bond Papers Project, an ongoing effort of the Carter G. Woodson Institute and the Center for Digital Editing. (Photo by Andrew Shurtleff)

The project will celebrate its public launch on Feb. 22, from 4 to 5:30 p.m. in Minor Hall 110, with a panel discussion on Bond’s speeches, moderated by McDowell. Panelists include Kevin Gaines, the inaugural Julian Bond Professor of Civil Rights and Social Justice and associate director of the Woodson Institute; Derrick P. Alridge, Philip J. Gibson Professor of Education in the School of Education and Human Development and director of the Center for Race and Public Education in the South; and Phyllis Leffler, professor emerita of history, who co-directed the “Explorations in Black Leadership” oral history project with Bond at UVA.

The project, and availability of Bond’s speeches online, offer young scholars and activists the benefit of Bond’s vision of civil and human rights, Gaines said recently.

“As struggles to defend basic civil and voting rights, human decency and multiracial democracy remain urgent, Bond’s papers offer a wealth of insight and a beacon of hope to people of all ages and backgrounds working to achieve a more just society and world,” Gaines said.

In an address to the Psychiatric Association Conference in Atlanta in 1978, for example, Bond addressed the concept of “color-blindness.”

“In days of yore, when Jim Crow still was king, color-blindness was gospel for reformers and anathema to racists. But when legal equality arrived, and economic justice also seemed to be in the offing, the racists adapted,” Bond said. “They suddenly embraced color-blindness and used it as a shield of philosophical and constitutional respectability behind which they could hide. ... Given the bitterly unequal situations of white and non-white Americans, the idea of color-blindness is pernicious fraud. It denies reality and sets a trap for many well-intentioned people.”

The project began five years ago with a crowdsourced transcription effort, called “#TranscribeBond,” that was held a second time the following year. Although the COVID-19 pandemic prevented subsequent public events, the transcription process has continued with online volunteers, McDowell said.

The project website owes its visual design and technical maintenance to project developer Erica Cavanaugh. With additional input from Jennifer Stertzer, director of the Center for Digital Editing, along with the staff there, the website allows simultaneous data storage and active editing.

The project aims to digitize all 47,000 documents in the collection, organized in 11 series and more than 1,600 folders, as well as to produce a scholarly edition of “The Essential Julian Bond.” If the project can secure full funding, that process should take another 15 years.

Bond, right, and his wife Pam Horowitz watched the 2008 election of the first African American president, Barack Obama, with UVA onlookers, including Dr. Marcus Martin, left, former vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion. (Photo by Jane Haley, University Communications)

“We examine every manuscript in the Special Collections Library, scan it with archival camera equipment and confirm image quality,” Baker explained. “We then upload it to a digital database before we transcribe, proofread, contextualize and ensure that the manuscript is searchable.”

From his years at Morehouse College organizing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Bond embarked on a multifaceted career in politics and social activism. He participated with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1963 March on Washington, served in the Georgia legislature for 21 years, became the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center in the 1970s and chaired the national NAACP from 1998 to 2010.

Bond, whose work spanned five decades, extended his activism to include LGBTQ rights and environmental causes. He received a Library of Congress Living Legend Award, among many other honors, before his death in 2015.

During his 20 years teaching in UVA’s Corcoran Department of History, Bond reached more than 5,000 students, drawing on his firsthand knowledge of the civil rights movement and its participants to situate their work in the larger context of American history.

At the University, the “Explorations in Black Leadership” oral history project that Bond co-directed with Leffler, started in 2000. The project culminated with a book, “Black Leaders on Leadership: Conversations with Julian Bond,” and a companion Explorations in Black Leadership website that features the video interviews Bond conducted with 50 subjects, plus Leffler’s interview of him.

Bond also participated in a range of UVA-sponsored events, from making remarks at annual Martin Luther King community celebrations to regaling guests at intimate dinners in faculty and staff homes, sponsored by the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion division. Over nine years, he also led annual tours of civil rights landmarks in Georgia and Alabama.

A six-story residence hall for students, located at the end of Brandon Avenue and adjacent to the University’s South Lawn, was named Bond House in 2019.

“Bond’s speeches constantly underscore the fact that we have to participate in our democracy, or we will lose it. We are reminded of this every single day,” McDowell said. “What does democracy look like? What forms can social activism take? Julian Bond gives us a provisional blueprint for all of these things.”

We’re here to answer your questions! Contact us today.