Grad Students Travel to Chile for Commissioning of Innovative New Astronomical Telescopes

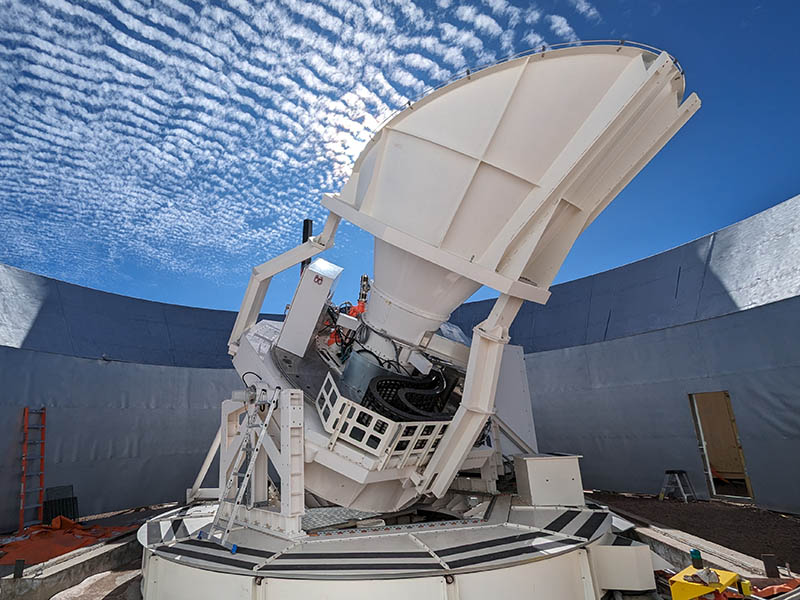

This spring, three graduate students with the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences' Department of Astronomy travelled to the Simons Observatory on the stratovolcano Cerro Toco, 17,000 feet above Chile’s Atacama Desert, to commission telescopes developed by the department with the help of a $53 million grant from the National Science Foundation. The project is making it possible for students to work with technology so sensitive it can observe remnants of the beginning of time.

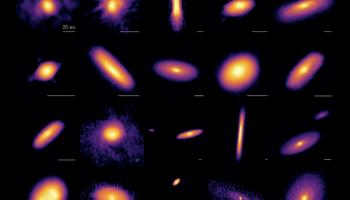

Rather than study the stars and planets, cosmologist Bradley Johnson, an associate professor of astronomy at UVA, is interested in the regions of the night sky that appear to be empty. To the naked eye, and even to the world's most powerful telescopes, those regions are black, but the electromagnetic waves that can be found there contain detailed information about what was happening in the universe in its distant past.

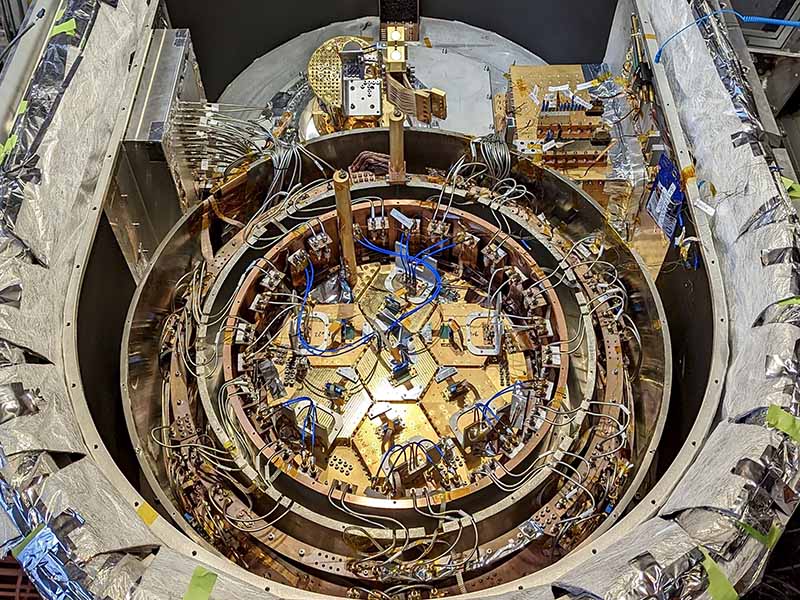

Funding provided by the NSF provided major infrastructure upgrades for the newly dubbed “Advanced Simons Observatory” in Chile, which includes innovative superconducting detector systems Johnson’s team helped develop that function at a temperature of close to absolute zero, or -459 degrees Fahrenheit. If the detectors work as planned, they should be able to detect extremely faint signals created as far back as a fraction of a second after the universe began, Johnson explained, and they may lead to additional breakthroughs in the scientific instrumentation used in both astronomy and physics.

After an eight-year process of building the telescopes and their camera systems and installing the detectors Johnson’s team helped build, Department of Astronomy grad students Jordan Shroyer and Liam Walters, along with machinist Peter Dow, currently a graduate student in UVA’s department of engineering spent nearly a month at the high-altitude facility commissioning the instrument and helping make its first-light observations – some of the first observations a telescope makes after it has been constructed – to make sure the instrument is working optimally. It’s the first step in a project that could run for approximately ten years, providing graduate and undergraduate students with extraordinary opportunities to be involved in research that will provide them with advanced skills in quantum computing, device physics and cryogenics.

The opportunity may also give students the chance to make significant contributions to science that could change what we know about the universe and its creation.

“If we can detect those signals left billions of years ago, then we’ll be able to test physics for the first time at the very beginning of the universe,” Johnson said. “It’s mind-boggling to think that we might be able to probe that far back in time and do experiments.”

“Being able to use my skillset to contribute to work that could answer some of the most pressing questions about the origin of the universe is not only exciting and personally gratifying but also feels like one of the most meaningful contributions I’ve made to human knowledge,” said Peter Dow, a grad student with Johnson’s team who serves as a senior machinist with the Department of Astronomy. “I hope with our contribution to this collaboration that UVA Astronomy will be seen as continuing a legacy of expertise, service and quality in delivering cutting-edge instrumentation to the greater astronomical community.”

For Christa Acampora, dean of the College, the work of Johnson and his students is an example of the school’s commitment to providing its students with a world-class graduate education.

“In Arts & Sciences, we take special pride in supporting students and faculty who collaborate on leading- and cutting-edge research. It's hard to imagine something more cutting-edge than seeing the first moments of the universe, and we're all in awe of Professor Johnson and his team as they work toward something so meaningful,” Acampora said.

We’re here to answer your questions! Contact us today.