The New Sound of History

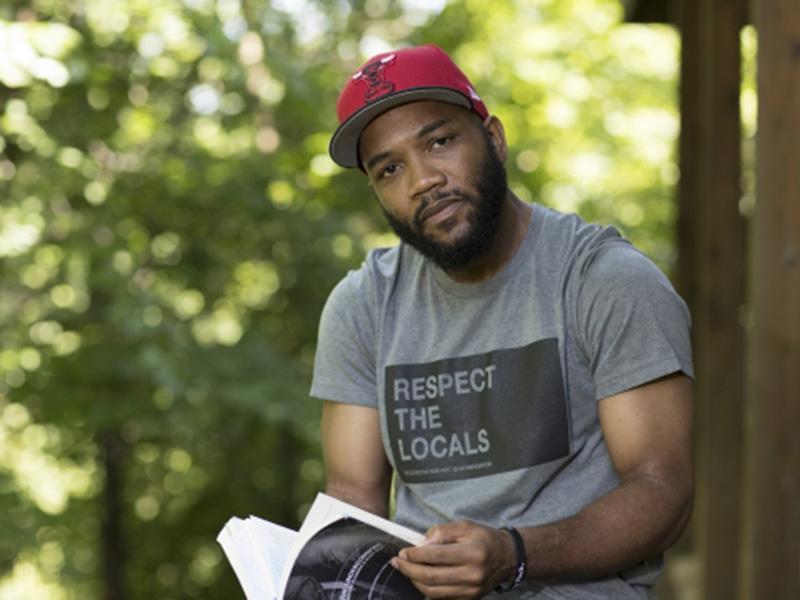

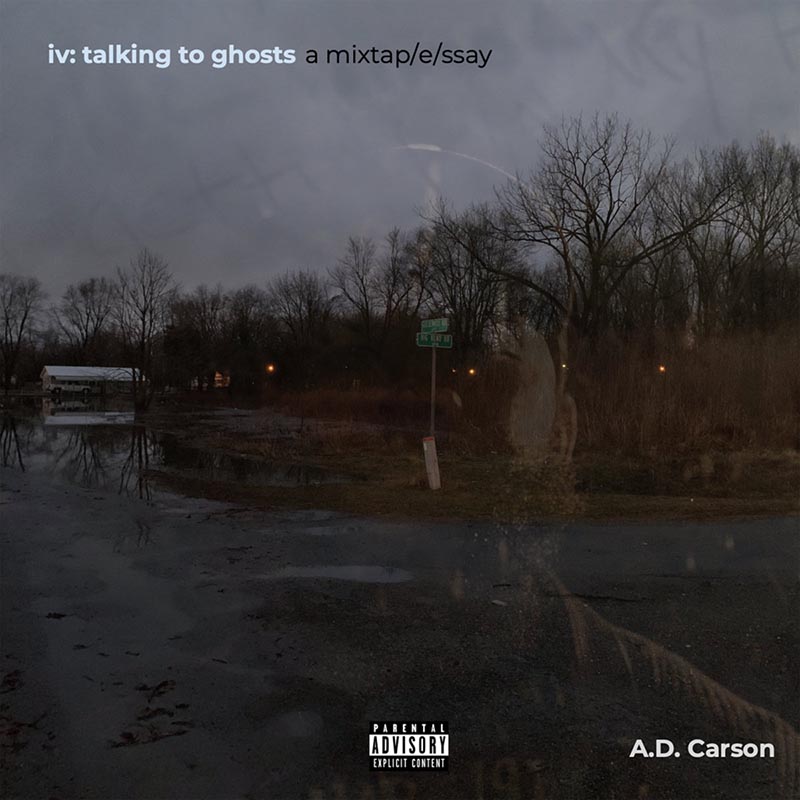

Earlier this year, rapper A.D. Carson, the University of Virginia’s assistant professor of Hip-Hop and the Global South, released his fourth album “iv: talking to ghosts .” This month, the album will be re-released along with an essay Carson has written to accompany it through Scalawag Magazine, a publication dedicated to oppressed and marginalized voices and communities of the South.

An innovative scholar and performance artist, Carson submitted a 34-song rap album, “Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions,” as his dissertation as a Ph.D. student at Clemson University. In 2020, his album, “i used to love to dream” became the first peer-reviewed rap album to be published by a university press. Carson’s unique brand of scholarship, dubbed “mixtap/e/essays,” pushes the boundaries of conventional research in search of a form of historical narrative that is both more inclusive and deeply personal.

The album “iv: talking to ghosts” was written during the COVID-19 lockdown and amidst worldwide protests against the deaths of Black people at the hands of the police and uses hip-hop as a medium for navigating and documenting the emotional toll of those events and the loss of family and friends during that time.

A&S Communications spoke with Carson about the album and the role of hip-hop in his work as a scholar and a professor.

Q: How would you set up the new album for somebody who is about to listen to it for the first time?

A: I’ve been asking the same questions for a long time, and those questions are about what access looks like in academia, what academic knowledge like history looks like and who gets to produce it. This album is more personal because it’s attempting to do a lot more of the work to intervene in the logic of the kinds of histories that we consider official. In other words, who are the kinds of people who become a part of the historical record? Is it my grandmother, who’s no longer here, or my cousin who passed away during the pandemic? Is his story going to be counted, or will it be lumped in with the millions who died? And who gets to make those kinds of choices, and what are the politics of those choices?

You can imagine how that resonates during a time in which Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were killed. The weight of it all becomes too much. Folks are dealing with the heaviness of being locked down and being worried about what’s happening during the pandemic with absolutely no clue about how we’re going to feel our way through it, and then this seemingly state sanctioned violence is continually going on like nothing whatsoever will stop it, not even a global pandemic. The suffering is a public thing, but it’s also intensely private. That’s the setting for the album. In other words, who do we listen to when the history of this moment is written about?

I mean, there are millions of people who have died, but it gets messier when you talk about the individual stories of the people who are gone and how that affects all of us. It almost seems cruel to put this ridiculously large number there and say this is what happened because that doesn’t really describe the enormity of it. So how do you get into the spaces to make some of that real?

For me, it has always been by trying to sonify it, to make to make music about it, to make music through it and to make music with it.

Q: What does someone who’s new to your work need to know about it?

A: I don’t know if there are any prerequisites. My approach to making music hasn’t been affected that much by being an assistant professor and being in academia because the questions that I’ve been concerned with predate that.

When I wrote the book Cold and an album, meaning for them to go together, one of the things that I kept getting as feedback was that people were seeing it as a book with a soundtrack, and I think that changes the way a person would engage with it. But I don’t know that you really get the stories the way they’re supposed to exist without the music, so what I’m really interested in is the container and how it might be able to hold the ideas and the emotions that we’re trying to get at, whether they be academic ideas or just really big emotions. Is a rap song an adequate container for it, or is an essay?

And this work of pushing back against genres is really me thinking about bodies, about what kinds of bodies are allowed in various spaces, and how is the way that somebody perceives your body affecting the humanity that you are afforded?

The analog is the way that we’ve put so much priority on forms like sonnets, sestinas or villanelles but not on raps to convey information or as a way to convey certain emotions in academic spaces. I really want to completely mix that.

Q: Is there one track that stands out for you?

A: The song “above” contains the last conversation that my cousin, my brother, a couple of my cousins, my nephew and I were having. We were standing outside on the land my grandmother used to own. The cover of the album is a picture of that land. It’s dark out there, and it’s raining, and we were all at a funeral, and we decided to go by and pay our respects and see our grandmother’s and grandfather’s headstones. When things like that happen, I’m often prone to take my phone out and start snapping pictures, and I also recorded some audio.

In that conversation, we were laughing about learning to play basketball, the milk crate hoop that we had and the wood plank that we nailed it to. So, as I was trying to write the album, I kept trying to write essays. I thought the work that I needed to do was to try to explain away everything that was going on. I tried to write about Decatur, Illinois. I tried to write about my relationship and conversations with the historian James Loewen. I tried to write about why I wrote my album “i used to love to dream.” I tried to write about how and why my family got to Decatur. I tried to write about the fact that the city of Decatur decided that it would not legalize the sale of marijuana even though the town was one of the ones that was disproportionately affected by the so-called “war on drugs.” I was trying to wrestle with all of these things, and if you listen to the album, you’ll hear lots of those things come out in the content of the album. But it was because I kept trying to write those things as essays and they didn’t want to be essays that made me realize I couldn’t capture in prose what I could in song.

So, I was flipping through the pictures in my phone and then that audio comes on from the time that I had last seen my cousin, and I hear his voice laughing and we’re joking, and I thought there’s no transcribing this. It can’t do the same thing that allowing people to hear this might do. So that clip is in the song, and I am grateful for whatever urge I felt to capture that moment.

And the album is loaded with moments like that: letting the work be what it wanted to be rather than trying to control it and make into something that would not accurately depict what I felt or what I was going through.

Q: Decatur is clearly a presence in the album. How would you describe the part it has to play?

A: Before he passed away, the historian James Loewen and I communicated several times. He grew up and went to school in Decatur, and then he went on to write Lies My Teacher Told Me and Sundown Towns, and doing all of this really important work, and he was a really important influence on the way that I think about history, and about how I think about the ways that we might be able to intervene and listen to what’s not on the page in order to be better about the ways that we write histories. In one of our last exchanges, he said that Decatur is one of the most sociologically significant cities in the country. My suspicion is that has something to do with race and class, and I feel that there’s not nearly enough of that that deals with people like me or my family, and I wanted to be sure that among all of that writing that gets done about Decatur that there is space for folks who sound like the Decatur I remember and that I experienced.

Q: What kind of response have you gotten so far?

A: The response has been interesting. I’ve gotten lots of responses from folks in Decatur, and I think I’m proudest of the ones that say that playing the album reminds them of growing up and living in Decatur. The challenge of doing this album independent of an academic press as I did with the previous album has been that it’s been slower to circulate. But I’m okay with that because there’s no expiration date on the content.

And it has been encouraging to hear that it resonates with people in some of those ways that I wanted it to resonate, like having my brother listen and confirm my suspicions about our shared feelings. I think that those are the kinds of things that make me feel like it’s accomplishing what I wanted it to accomplish. But there’s still more writing that I have to do about the album. I’ve written an essay that I believe should go along with the album that I think would really be helpful for folks to listen to or engage with if they’re listening to the album.

I have also been talking to an editor at the University of Michigan Press about making all of these things available eventually, after the album goes through their peer review process. Then they’ll be able to catalog it and archive it and then have all of these things available there, but I wanted the work to be public first so that when people were engaging with the work there wasn’t a veneer of novelty of a rap album being published by an academic press detracting from the very serious and deeply earnest subject matter that the album is attempting to tackle.

Q: How does the album factor into your role as a teacher?

A: Well, I’m asking my students to work at the level of the of the things in the world that they have something to say about, so I ask them to engage in a process very much like the process that I engage in whenever I’m making music. We’re reading widely across disciplines, we’re listening to a number of different voices and to one another, and we’re trying to shape what we come up with into music that will be representative of how we have chosen to engage with whatever is there, whether it be a text or with other people.

And so, while the content of what we do may be vastly different, because the content of our lives is so different, the methodology is very similar. That can be challenging for students, to hear that whatever you feel like you need to make or whatever you feel moved to make is the thing that you should be making. That’s so much different than me saying they need to write a five-paragraph essay or a 2,500-word paper. I want to know why you were moved to make whatever it is that you’re going to make and then help you as a student accomplish the thing that you set out to do. This means that I have to be flexible about teaching what the conventions of particular things are, and we have to be receptive to learning those conventions and how we might be able to push back against them because they’re kind of guideposts they’re not law. The question is what do you want to make and what do you need to know to make it. And that can be hard.

In the same way that it’s difficult for me to feel my way through — and I’ve been doing this for my entire professional career, and it’s still really difficult — for some of my students it’s the first time. It’s the very first time they’ve been given free rein to do whatever it is they want to do, and it’s challenging, but I believe that they appreciate the freedom and they appreciate having someone listen to what they want to do rather than telling them what they should be or how they should be.

Q: You’ve won some awards recently. Could you tell me about those and what they’ve meant to you?

A: The Association of American Publishers gave “i used to love to dream” their award for best eProduct. It also won the Research Award for Excellence in the Arts and Humanities from the Vice President of Research here at UVA, and more than what it means to me, I hope that it’s encouraging to people who want to do hip-hop focused work and want to make rap music and offer it as a kind of academic scholarship at places like the University of Virginia, where it’s not only welcomed but appreciated by your academic colleagues. That shows, at least at some level, the value that’s placed on showing up the way that you are and offering what you have to offer and the institution recognizing that it is something it welcomes and honors.

I think it’s the same with the Association of American publishers. I imagine that it makes it a lot easier for a place like the University of Michigan Press to think about different ways that scholars or artists might present their work. Hopefully, other publishers will look at it and say that this is important work, and it is contributing to the future of knowledge production at a time when lots of institutions are signaling that they are more receptive to hip hop and other kinds of knowledge making and when so many artists are being acknowledged and being brought in to do this kind of work in academic institutions. I hope this pushes academic institutions to commit the kinds of resources that are necessary to do the very serious and very meaningful work of changing how the institutions look at knowledge making.

But it’s humbling and very important to me that my colleagues here at the at University of Virginia acknowledge how this might work and how this is pushing the boundary in a direction that could be important for the future of academic work.

Q: You have also been writing essays for the media recently. What are some of the subjects you’ve been writing about?

A: I wrote an article about the overlap between the history of rap as a category in the Grammy awards for The Washington Post, and I wrote something about “i used to love to dream” for NPR’s Code Switch. I also wrote about scapegoating rap more recently for The Conversation after the mass shooting that happened in Highland Park. People there described the alleged shooter as a rapper, which seemed really odd to me that rap would have anything to do with why he committed the crimes that he’s alleged to have committed. I also put together a playlist for The Conversation focused on reproductive justice to showcase the ways that rap has been engaged in those kinds of topics.

I also wrote an essay for Inside Higher Education about how more college students should study rap. It would be really helpful for people to have some proficiency with kinds of messages that are that are appropriated from hip-hop culture. I think that that might help us think about our conversations, about politics, like thinking about Critical Race Theory, what it actually is and the ways that people have deployed that term to mean something that it’s not and thinking about the way that histories get written and who they get written by and thinking about elections and school boards and what becomes part of the curriculum.

I think that there are ways that we might be able to apply a hip-hop framework to think about those things. It’s such fertile ground for us to be able to do the kind of work that we want our students to be doing and engaging in the ways that we want citizens to be engaged. We know the incredible influence that hip hop has had not just here in this country but all over the world, and it works as a really easy and accessible common text. I think that it’s time we start thinking about how we equip not just young people but how we equip all people in society to be able to have these discussions, and I think that hip-hop might have a lot to say about that.