Does Dunking Your Head in Water Ease Anxiety? Ask This Professor’s Diving Mice

Face dunking for anxiety – yeah, it’s a thing that surfaces frequently on social media. But is it a real thing?

Proponents say plunging your face into an ice-cold bowl or bucket of water serves as a quick fix to prevent brain freakout before a stressful situation. They even claim there’s science involved – something called “the diver’s reflex.”

The idea is that when your nostrils and face get wet, and you hold your breath, a survival instinct kicks in to calm you and conserve energy. Involved in the process, they say, is a bit of biological circuitry called the vagus nerve, which connects the brain with the gut.

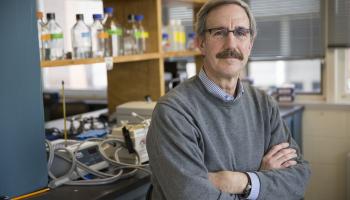

UVA Today checked in with assistant professor of biology John Campbell, whose neurobiology lab at the University of Virginia studies the vagus nerve, to see if such claims hold water.

Q. There is a social media trend of “face dunking” to calm anxiety. Does it work?

A. I do think there’s truth behind that. Holding your breath and putting cold water on your face, or just an ice pack, will trigger the diving reflex, which dramatically decreases your heart rate. Essentially all mammals have this reflex, from mice to humans to blue whales, which likely helps us stay underwater longer.

Interestingly, recent research has shown that heart rate alone can affect anxiety, specifically that increasing heart rates in mice causes them to act more anxiously. Ongoing research in my lab suggests the opposite may also be true – that decreasing heart rate can decrease anxiety. So, triggering your diving reflex will decrease your heart rate, which may make you feel less anxious.

Q. How does that relate to the vagus nerve?

A. The vagus nerve is a vital conduit of information between your brain and body. Many of the nerve fibers that make up the vagus nerve carry internal sensory information from your body to your brain, telling your brain, for instance, that there are nutrients in your gut, or that there's a change in blood pressure.

However, other vagal nerve fibers transmit signals from brain to the body. These descending nerve fibers control many of your other organ systems, including the cardiorespiratory, digestive and immune systems.

The diving reflex is one important reflex controlled by the vagus nerve, specifically by the vagal nerve fibers that go from your brainstem to your heart and slow its rate. There are many other reflexes that help the brain adapt organ function to the body’s ever-changing needs.

Q. Why is our brain wired to our gut, and in a way that also seems to relate to mood?

A. The vagus nerve tells the brain what’s happening in the gut, from the presence and type of nutrients to whether there is an infection. The vagus nerve may also be sensing signals, directly or indirectly, from the gut microbiome, which is impacted by diet and stress and can affect our mood through the vagus nerve.

Of course, the vagus nerve carries information in the other direction, too, from brain to gut. This brain-to-gut signaling helps the body digest and absorb nutrients while preventing dangerous rises in blood sugar after a meal. Unfortunately, this system breaks down in a variety of diseases, from Parkinson’s to diabetes. My lab is working to understand how it normally functions so that we can know how to treat it when it breaks down.

Q. Tell us more about your lab’s interest in the vagus nerve.

A. We are fascinated with how one nerve can have so many visceral functions, from decreasing heart rate, to managing blood sugar, to moving food through the gut. How is this system organized? Are there certain nerve fibers that, for instance, only decrease heart rate, and others that only increase insulin secretion from the pancreas? If so, how are they connected in the brain, how do they signal and how can we target them to treat heart disease, diabetes and anxiety disorders?

Q. Can you talk about your latest research with diving mice? Aren’t they afraid of water?

A. One of our ongoing projects is studying the diving reflex in mice to better understand the neurons involved, since they powerfully control heart rate. To naturally induce this reflex, we are training mice to voluntarily dive underwater and swim under a barrier, an assay that was developed by a previous undergraduate researcher in our lab, Veronica Gutierrez, working with our collaborator, professor Steve Abbott, in [the Department of] Pharmacology.

Assistant professor of biology John Campbell is the principal investigator for the Campbell Lab. He’s also associated with the UVA Brain Institute. (Contributed photo)

To make the experience less unpleasant for mice, we keep the pool water bathwater-warm. Still, when they dive underwater, we see their heart rate slow to about 25% of resting rate, a really striking change. While I can’t say whether the mice like this activity or not, some will climb out of the water and then turn around and dive back in. All the mice we’ve studied so far have learned to dive and show a robust diving reflex.

As for mice being afraid of the water, I’m not sure why that’s the case. I suppose it could be related to maintaining their body temperature. Mice must use a lot of energy to prevent hypothermia and lose insulation when they get wet. For our diving mice, we keep the pool water warm and give the mice a warming lamp to help dry off after diving.

Q. What are you learning from your recent research?

A. Research in our lab and others is shedding light on the organization of the vagus nerve and how it controls heart and digestive functions. My lab has found that genetically distinct subtypes of neurons in the brainstem connect with different visceral organs through the vagus nerve, to control different organ functions.

While our diving studies are not published yet, our study shows that activating the descending brain-to-body nerve fibers of the vagus nerve decreases heart rate and anxiety in mice.

This research, led by a doctoral student from the neuroscience graduate program, Nicholas Conley, and a former undergraduate researcher, Lily Kauffman, is currently in peer review. Our research on the diving reflex was led by former undergraduate researcher Veronica Gutierrez, biology doctoral candidate Maira Jalil, and a former pharmacology doctoral student, Tatiana Coverdell. It will be submitted for peer review soon.