New Album Remixes Traditional African Music for the Electronic Generation

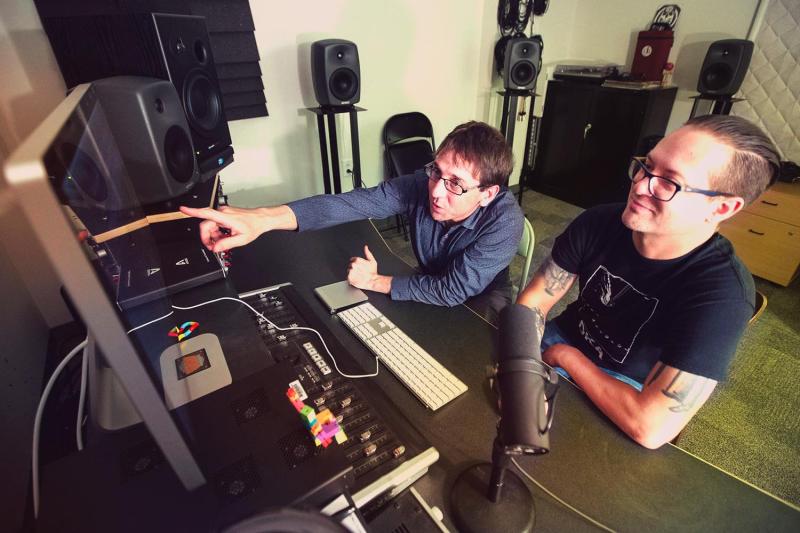

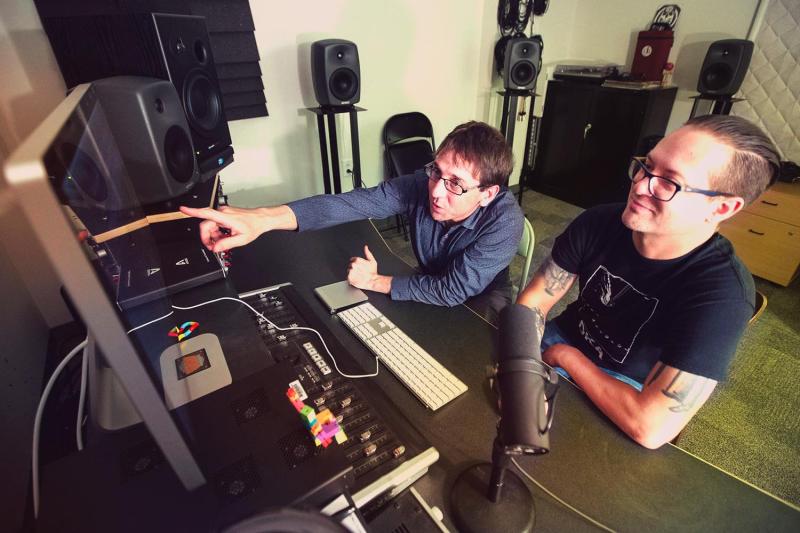

UVA assistant professor (and former DJ) Noel Lobley’s association with sub-Saharan Africa began in 2001 with a donkey cart and a few fellow musicians traveling South Africa’s townships to play recordings of traditional African music.

Fifteen years later, Lobley is now linked with the Beating Heart project, working with musicians – from the little-known to the already-famous – who are remixing those recordings for an internationally acclaimed album released Friday in London.

“The Beating Heart – Malawi” features 21 songs that sound as contemporary as any Top 40 anthem. Musicians include local artists from Malawi and international contributors like the British band Rudimental (whose fans include Jay Z and Beyoncé), with support from major production companies like Sony. A biopic and feature film are in the works, as well as many additional albums and partnerships with innovative local and international charities.

Even amid this international fanfare, however, the heart of the project remains distinctly African, a tribute to the streets Lobley and many other musicians have wandered and the villages where the original recordings were made.

The project is based on more than 35,000 recordings of traditional village music in Malawi and 17 other southern and central African countries, recorded by English ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Lobley, who joined UVA’s McIntire Department of Music this year, was in awe when he first heard Tracey’s collection.

“The sound was just overwhelming. I initially responded to its spirit purely as a musician, and a listener and then as a DJ and sound artist,” he said. “It affected me enough to ultimately go live in South Africa. I wanted to find out more about what the music was.”

Many artists now involved in the Beating Heart organization were similarly moved and are donating their time and talents simply because they love the music, Lobley said. Proceeds from the first album will go directly to African communities through Beating Heart’s associated Garden to Mouth project, building sustainable food gardens at schools in Malawi.

“When I see the roster and the profile of artists who have agreed to work with us for nothing, it’s amazing,” Lobley said. “These are not people who need more projects. They are people who need the right projects. They get the value of what we are trying to do together.”

Humble Beginnings

For Lobley, the project began when he discovered that Tracey’s recordings were little-known except among scholars working with the archive Tracey funded, the International Library of African Music in Grahamstown, South Africa.

“Almost none of the local musicians or artists knew that there was this heritage recorded by some of their relatives or ancestors,” he said.

With the archive’s permission, Lobley began sharing Tracey’s recordings with hip-hop and house artists that he deejayed with in South Africa, who were eager to learn more.

“They were most interested in taking on the music, and shaping it and turning it into new art,” Lobley said.

That’s where the donkey cart came in. Lobley and South African artist Nyakonzima Tsana gathered musicians to learn the songs, hired the cart and traveled to various townships in the Eastern Cape to play and perform the recordings. They worked Tracey’s recordings into their local DJ sets, played them in theaters and schools, set up poetry readings and home listening sessions, and even piped it into taxis and bars. Actors also adapted the music into plays, using lessons from their ancestors’ songs to speak out against issues like sexual violence, which remains a pervasive problem in South Africa.

“It was really inspiring how you could activate this archived music in the present and make it a part of people’s daily lives,” Lobley said.

An International Stage

Though he remained connected to efforts in South Africa, Lobley returned to Oxford University in 2010 to complete his Ph.D. and become a sound curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum. There, he met musician and filmmaker Chris Pedley, who sought Lobley’s expertise for his documentary on Hugh Tracey.

Pedley, whose wife Lisa is Tracey’s great-niece, shared Lobley’s fascination with the recordings. Together, they began to share Pedley’s dream of creating albums featuring remixes of Tracey’s recordings made by both African and international artists.

That’s when they met Oliver Moira, co-founder and former owner of the London-based label Black Butter Records.

Pedley met Moira while volunteering with an orphanage in Malawi and told him about Tracey’s archive. Moira, who had already spent several years working with communities and musicians in Malawi, was immediately interested and later met Lobley in London.

“I thought it would be an hour’s meeting, but we ended up hanging out most of the weekend,” Lobley said.

Pedley and Moira came together to form the Beating Heart organization and decided to begin the project in Malawi. Moira offered to use his industry contacts to connect high-profile artists with local artists, set up a record label and raise funding.

Milestones followed in rapid succession. Major artists in Africa and beyond signed on. A fundraising concert on the shores of Lake Malawi generated buzzing public excitement. Determined that the project would give back to the local community, Beating Heart linked up with its associate charity, Garden to Mouth, to give artists a cause to rally around in the midst of an ongoing drought that has left about 2.8 million Malawians worried about their next meal.

“I think many people are attracted to the idea of a socially responsible record label and organization in an industry that can be vicious and money-grabbing,” Lobley said. “People have reacted against that, and part of this project seems to be seeing a different future.”

Lobley is adamant that everyone involved remained closely connected to the Africa that is at the heart of the project. Thanks to Beating Heart, many of the international artists have visited Malawi to meet local musicians, begin to learn about the culture and visit schools benefitting from the album’s proceeds. Lobley, Moira and Pedley also regularly spend time in Malawi and throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

“You have to be so careful not just to do top-down projects, and you can only do that if you spend lots of time listening to local people. If you don’t, then you always get it wrong, in my experience,” Lobley said. “I hope this will show the way forward for curation sound projects and for genuinely collaborating even when you are operating with a power differential.”

He is also determined to maintain the academic integrity of the project and closely involve UVA scholars and students. He hopes to create a visiting residency for African ethnomusicologists who would like to come to UVA, and to involve students in the Beating Heart project, both on Grounds and during study-abroad excursions.

For now, though, his efforts are focused on promoting the new organization, which is currently circulating through events in the United Kingdom and Europe and will come to the U.S. and back to Africa. He is also looking ahead to the next Beating Heart album, which will be created in South Africa and benefit organizations championing women’s rights.

For Lobley, it will be a trip back to where it all began.

“South Africa is where it started for me, and I think it could be a game-changer,” he said. “It excites me, what this could be. I think it could be really, really big.”