Science’s Silent Stars

Scientific breakthroughs don’t happen overnight, and they’re rarely the work of just one person. At top-rated research universities like UVA, the process of discovering new knowledge about the world can take teams of students and researchers working together for months, years and even decades to advance the boundaries of scientific knowledge. And while research faculty, post-docs and students deserve credit for the insights their labs make possible, some of that credit belongs to university research teams’ most often overlooked member: the lab manager.

From providing the essential day-to-day administrative support university labs need to function safely and efficiently to bringing continuity and consistency to work that needs to move forward while grad students, undergrads and post-docs come and go, the work of the lab manager is essential to helping research faculty stay focused on the big picture.

Meet some of the most important members of the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences’ research labs who are helping make scientific discovery a reality.

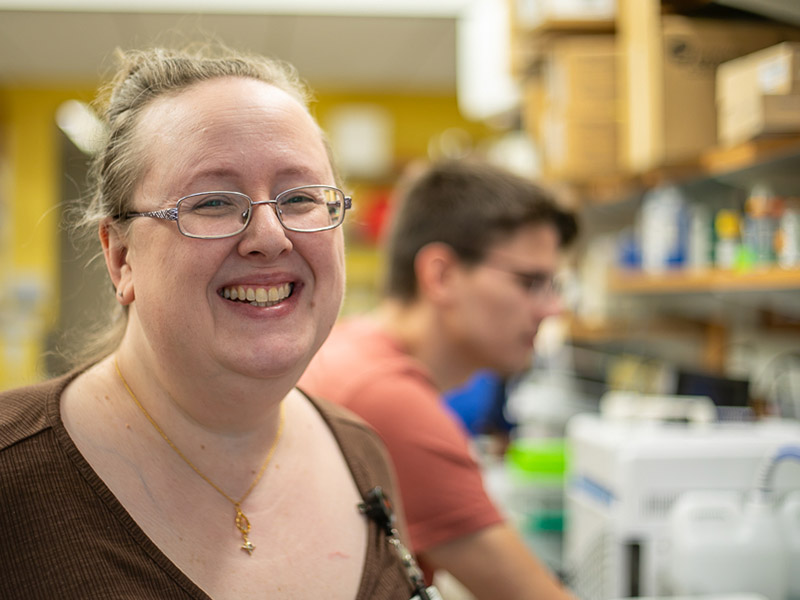

Michelle Warthan, Güler Malaria Lab

Around the world, malaria remains a major public health challenge with over three billion people at risk and half a million deaths annually. The organism that causes the disease has acquired resistance to every antimalarial drug on the market, and there is an urgent need to understand more about how that drug resistance develops.

Biology professor Jennifer Güler works to understand the cellular mechanisms that allow the parasite that causes malaria to survive and explores how genetic diversity within the parasite population affects its resistance to drugs.

Former high school biology teacher Michelle Warthan began her career at UVA as a lab technician in the UVA Digestive Health Center and now works as the Güler Malaria lab’s manager. Her work advances the team’s studies in metabolic adaptation and resistance initiation, but her role in the lab is much bigger than that.

“I do a little bit of everything,” Warthan said. “That’s pretty much what a lab manager does.”

In addition to working with the vendors that supply the lab with essential tools and equipment, Warthan is usually the first person the lab’s new graduates and undergraduates interact with, and her role is to teach them the skills they need to succeed in the lab, assess their strengths and keep them safe in the lab environment. That broad set of responsibilities gives her a unique perspective.

“Graduate students or lab technicians are usually focused on a single project, but as a lab manager, you have to have a much broader view,” Warthan said. “You have to be able to see how all of the parts are working together, and that’s the importance of having a lab manager: it makes the work of the lab much easier.”

Warthan is also working on a masters in 3D animation, which has made her a key collaborator in Güler’s Infectious Disease in 3D program that gives students the opportunity to design and build virtual reality environments that help them learn about biological processes that are too small to be seen.

“The Infectious Disease in 3D program presents a special opportunity for our students to leverage the rapidly growing domain of virtual reality-based animation tools,” said Arin Bennett, an information visualization specialist with the UVA library system who worked with Güler and Warthan to develop the program. “We are fortunate to have Michelle playing an integral role in the project. Her background enables her to assist the students in crafting content that is not only compelling but also accurately and faithfully represents biological functions.”

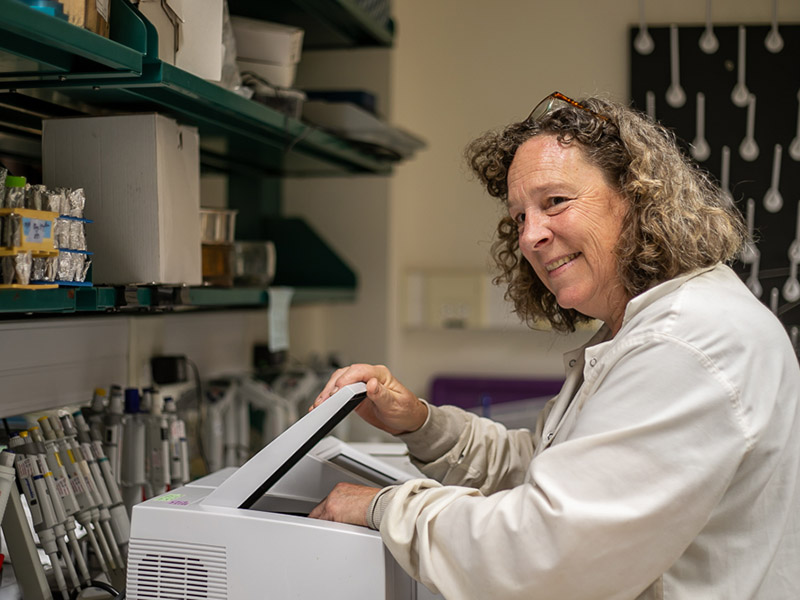

Susie Doyle, Siegrist Lab

One of 13 members of the College’s Siegrist Lab, Susie Doyle plays a dual role as senior research scientist and lab manager for a team focused on understanding the fundamental principles that govern the development of mature animals from single cells with the aim of providing new insight into methods that might be capable of restoring or replacing neural tissue damaged by disease or injury.

A neuroscientist and cell biologist with a Ph.D. from UVA, Doyle chose the path of a research scientist because it keeps her involved in research without the added responsibilities that can come with a faculty position or the stresses of being a principal investigator, the person in charge of a scientific research grant.

“I really love the research, and I love the academic environment,” Doyle said. “I have an office, but I don’t use it very much. Ninety percent of the time, I’m in the lab.”

The other 10% of the time, Doyle keeps the lab stocked with the supplies the team needs and makes sure they stay within their budget. She’s also a constant presence in the lab, which frees up the lab’s principal investigator, biology professor Sarah Siegrist, to teach, attend meetings and speaking engagements, and focus on writing grants and research papers.

“It’s really valuable for the lab members to have somebody there all the time,” Doyle said. “If they have questions, if the equipment isn’t working, they can always come to me, and that makes my position valuable for Sarah, because she can focus on the higher-level stuff that keeps the lab running.”

“Because Susie has been in the lab since the very beginning, she is an invaluable source of knowledge. She knows what does and doesn’t work experimentally and she knows other key details that are not always explicitly written or acknowledged,” Siegrist said. “On top of that, Susie trains the next generation of scientists at the bench. Susie has expert hands, and she passes on her knowledge and expertise to starting Ph.D. students, undergraduates and even post-docs. Our work really is a team effort, and Susie is an integral part of it.”

Having a dedicated research scientist or lab manager in the lab can also attract those students and post-docs to the team, Doyle believes.

“If you’ve had someone in that position for a long time, it’s a good indication that the lab environment is probably very good,” Doyle said.

Drew Latimer, Kucenas Lab

A typical research project for a graduate student or a post-doc lasts from two to five years, and hiring research scientist Drew Latimer gave Sarah Kucenas, a professor in the College’s Department of Biology and principal investigator with the department’s Kucenas Lab, the opportunity to launch a project with a much bigger scope.

Kucenas’ research is focused on the zebrafish, a small freshwater fish related to the minnow that provides neuroscientists with the optimal model for studying the genetic and cellular mechanisms related to the development of vertebrates, including humans, whose genomes are remarkably similar. Kucenas is interested in the role glial cells play in the development, maintenance and regeneration of the nervous system, a role she finds is much more important than scientists once thought. She’s concerned primarily with understanding fundamental cellular interactions, but there is the potential for the findings her lab produces to lead to breakthroughs in science’s understanding of diseases and disorders like multiple sclerosis and autism.

Latimer, a biologist who has studied zebrafish for most of his career, was hired by Kucenas to develop a long-term RNA sequencing project. He provides Kucenas and the graduate students and post-docs in her lab with the data they’ll need to make these discoveries.

Like many of his colleagues on Grounds whose roles also include lab management, Latimer also plays an important part in the culture of the lab by mentoring Kucenas’ students and helping them succeed, a job that best suited to someone who has the time to focus on the students and their strengths.

“I am truly lucky to be able to work with Drew. He is an exceptional scientist,” Kucenas said. “For our research group, he brings a wealth of experience, and everyone who comes through the lab doors interacts with Drew and values his advice and knowledge. But more broadly, he helps me mentor new members in the lab. For these junior scientists, this helps them achieve independence and autonomy really quickly.”

“It’s actually kind of fun,” Latimer said of working with students with a broad range of experience, from the graduate student who needs help with a DNA sequencing analysis to an undergraduate just learning how to hold a pipette. “You have to figure out where a person is at intellectually and then help them start where they need to start.”

Meg Miller, Virginia Coast Reserve Long Term Ecological Research Program

Meg Miller came to UVA with a master’s in biology and a background in wildlife biology. She has worked with several of the labs in the College’s Department of Environmental Sciences, and she is currently a lab specialist on the team of environmental science professor Karen McGlathery whose work as head of the Virginia Coast Reserve Long Term Ecological Research (VCR LTER) program focuses on climate change and the environmental impacts of rising sea levels.

As McGlathery’s lab manager, Miller purchases supplies and keeps the equipment in working order. She is also involved in water quality sampling and processing the water samples McGlathery’s team sends to Grounds from the Eastern Shore, which provides continuity to the processes that need to continue amid the constant change that semesters, school years and graduations bring. Her work processing tens of thousands of water samples over the last 20 years has played an important part in helping the VCR LTER understand how climate change is impacting Virginia’s shorelines and in helping the program develop innovative solutions some of the challenges Virginian’s will face as a result.

Miller also works closely with McGlathery’s students, helping new students understand basic skills, processes and safety procedures and answering their questions.

“I manage them and teach them what they’re supposed to be doing as a member of the team,” Miller said. “My job is to make it easier for them to do the work they need to do.”

“It can be a hard job,” Miller added. “Lab managers do a lot of different things, and it can be a really demanding job, both physically and mentally. I really like my job and feel really lucky because I have a great boss, and I work with great people.”

“Meg plays a critical role in the VCR LTER project, and we’re so fortunate to have had her as part of our team for more than a decade,” McGlathery said. “She’s an incredibly inspiring and supportive mentor for the many undergraduates who work as research assistants in our program. I have tremendous respect for her. She’s the glue that keeps everything together.”